TRUNK TALES

LEAVING HOME ... FINDING HOME

With the signing of the British North America Act in 1867, Canada’s new political leaders adopted the country’s official “National Policy” - a three-pronged guide designed to assist in the country’s development. The policy called for the construction of a transcontinental rail system, the adoption of an agrarian-focused immigration policy and the establishment of a protective tariff-system-based economy.

The uncertainty of life in Ukraine and the enticing prospects of life in this new country, set the wheels in motion for a profound migration of Ukrainian people from the densely populated European countryside to the sparsely populated Canadian West. What began in large numbers after 1890, started a migratory trend that has lasted for more than 125 years.

Ukrainians left their homes but came to Canada and found home.

First Period of Immigration 1890-1914

With the passing of the Dominion Lands Act in 1872, Canada became an especially attractive destination for settlement.

This Act guaranteed male immigrants aged 21 or older title to 160 acres of free land in Western Canada for a modest $10 fee. To gain complete ownership of the land, immigrants had to fulfill a number of requirements. Those were to cultivate at least 30 acres of the granted land, construct a permanent dwelling and to occupy the site for at least six months per year over a three-year period.

As the population of Europe was exploding, Ukrainians among other Europeans were struggling to survive, facing not only economic hardship but also cultural and political repression under the control of imperial authorities. The idea of having title to 160 acres of land was an astonishing opportunity.

Canada

200 million acres under management in western CANADA.

160 acres ‘Free Land’ for each Settler.

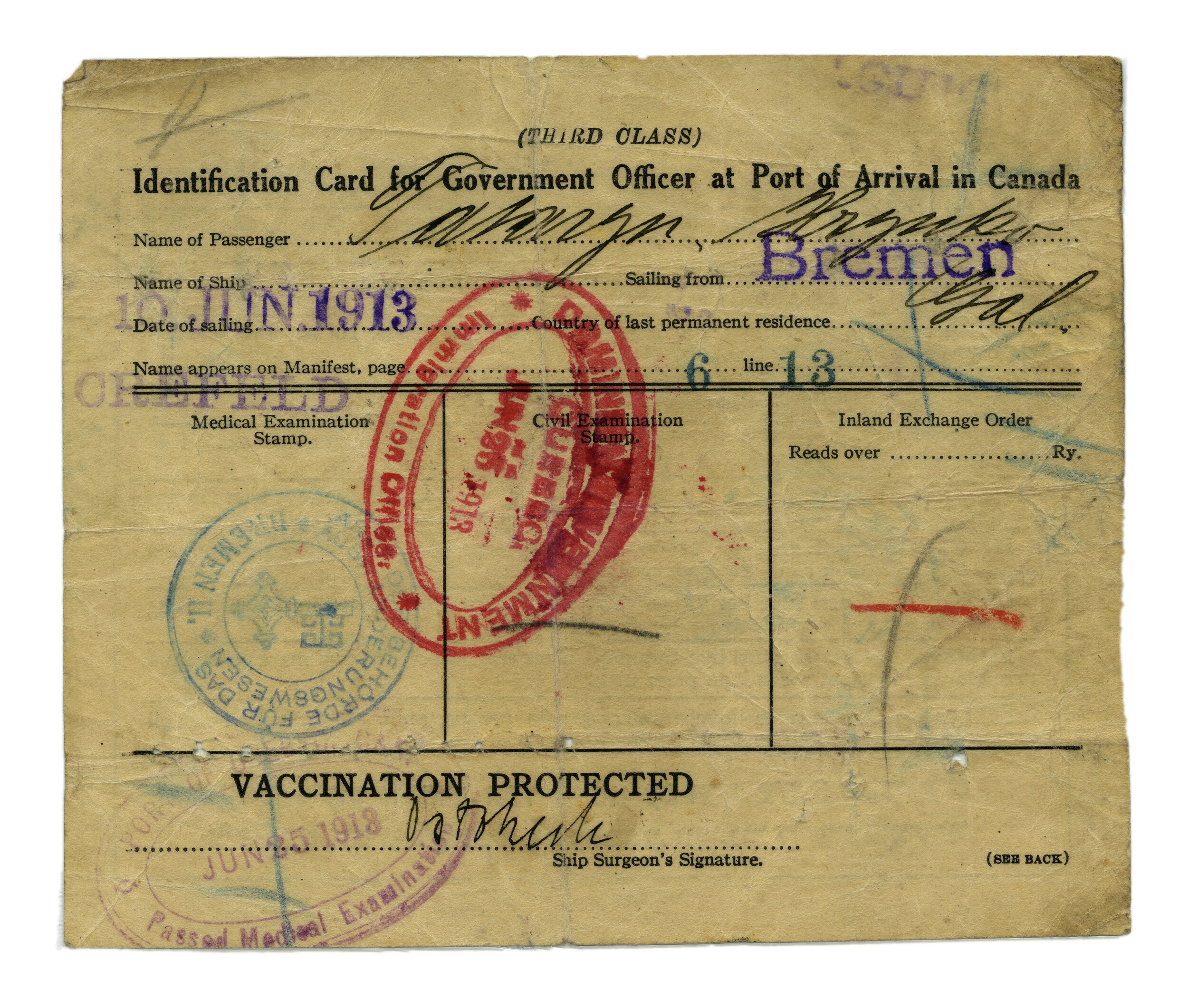

And so they left Europe and came to their new country of Canada. Many new arrivals endorsed Canada as a well-suited destination for settlement in correspondence with family and neighbouring villagers back in Europe. Passage from Europe to Canada was long and arduous as immigrants were herded into overcrowded steamships for the seafaring journey across the Atlantic Ocean. However, once in Canada, many found the rail transportation a welcome surprise as many new arrivals remarked on the comfort of the cars, equipped with ample space, heaters and bathrooms. Having finally arrived in Canada, now Ukrainians were forced to cope with the harsh reality of homesteading in the Canadian West or finding labour related work in other parts of the country.

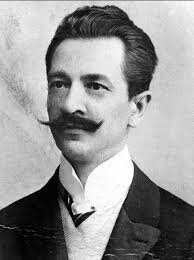

Dr. Joseph Oleskiw was a Ukrainian professor of agronomy who promoted Ukrainian immigration to the Canadian prairies. His efforts helped the initial wave of settlers who began the Ukrainian Canadian community. He made inquiries to Canadian immigration officials on conditions in Canada and even travelled to the prairies to evaluate Canada’s suitability. After visiting Canada in 1895, he wrote accounts of what he had seen in pamphlets O Emigratsii [About Emigration]. He provided information on the emigration process and the harsh realities prospective settlers would face in Canada, but as well positive observations: “The Red River soil was “so rich, that even without fertilizing, it will produce good crops” “In a few years the farmer will build himself a good livelihood”.

IMMIGRATION . IMMIGRATION . IMMIGRATION

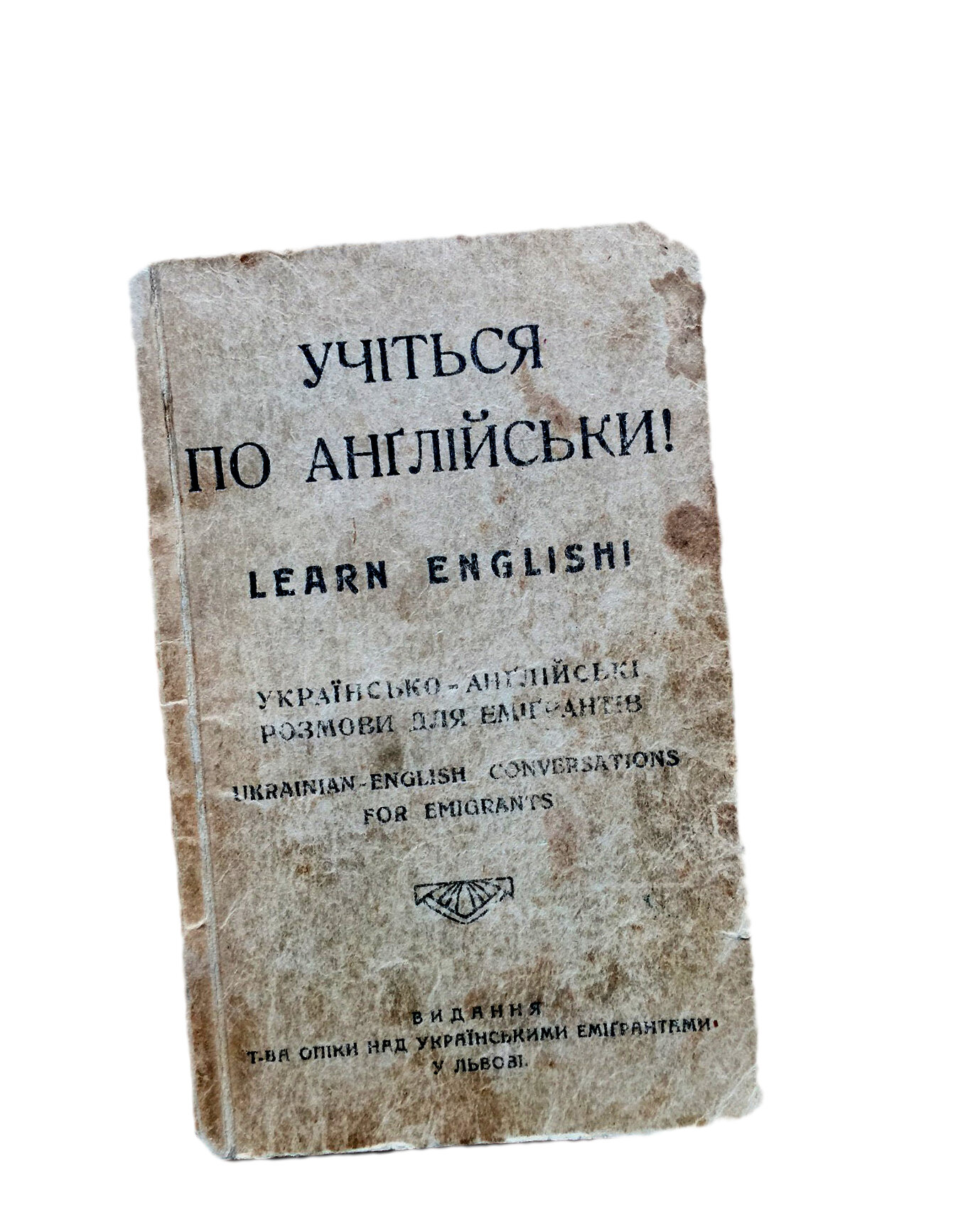

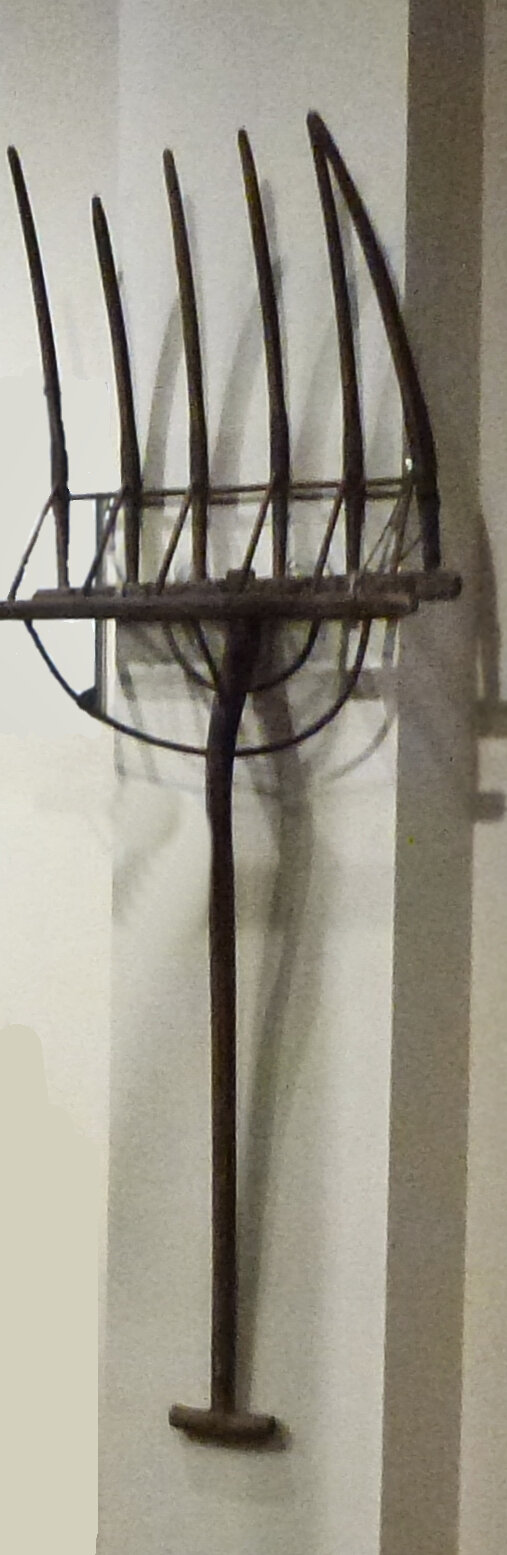

People were leaving Ukraine because they were looking for a better future for themselves and their children. There was no hope of prosperity or having land to divide among their children. Canada was offering the reality of a dream. They packed up personal belongings and along with that they brought small items that they could pack in a trunk; homemade tools, hammers, things of that nature. They also brought seeds; tobacco seeds, flower and vegetable seeds, grains.

They brought with them reminders of home: a snapshot, clothing, utensils that would help them start their life in a new world.

The vast majority of Ukrainian immigrants settled in Western Canada in a wide arc from south-eastern Manitoba to the Yorkton-Saskatoon district and along the valley of the North Saskatchewan river to Vegreville, east of Edmonton. They settled in close-knit communities to give each other material and psychological support in this new and inhospitable land. While most Ukrainians chose to homestead and farm the land many also became wage workers in resource industries in such places as Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia and Northern Ontario to work in the burgeoning mining and steel industries.

The Tataryn Family

Father John Tataryn’s maternal grandparents Matey Makiw and Kateryna Michalyshyn came to Halifax, Canada in 1912 with their young daughter. While working at the steel mills, Matey became ill and the company he worked for convinced him to go back to Ukraine to recuperate. Father Tataryn’s grandparents returned to Ukraine leaving their daughter (Father Tataryn’s mother) in the care of their neigbours in Canada as they didn’t have enough money to pay for her boat fare. Kateryna planned to come back to Canada but WW1 broke out and she was unable to return.

In the early 1900’s Canada was inviting Europeans to pioneer the prairies. However, many immigrants to Canada did not end up there. The steel mills and the mining companies needed workers badly as well and Sydney, Nova Scotia had a steel mill that actually employed over 6,000 workers, not counting the coal mines, which had many more workers. There were many Ukrainians and Polish people that clamoured for these jobs. Immigrants wrote back to their families in Ukraine, “Come, you don’t have to go to the prairies, I can get you work in the steel mill, coal mines, you’ll make money, and then you can buy land.” That was the way that it was done.

Journey to Canada Series | Fr.John Tataryn

Click above to view the interview. (26:01, English)

The Ukrainian community grew, built churches and halls where friends could congregate. A Ukrainian Catholic Church was built in 1912. A priest was dispatched from Montreal and asked to go a little further and find out what was going on in Sydney. The priest sent back a telegram saying “Я заїхав до кінця світу” (“I have come to the end of the world. The train can’t go any farther, there’s just the ocean”). An Orthodox church was eventually built, as well. The community tried to retain the Ukrainian culture as much as they possibly could and eventually established a рідна школа (cultural school) and a Ukrainian dance group. But all the ethnic groups in Sydney, worked together to maintain a community while trying to retain their own culture as well.

Wheras Father Tataryn’s mother came to Canada with her family, his father, on the other hand, came on his own in 1913. He was 17 when he left Ukraine, went to Germany to make money and then came to Canada. He ended up in Winnipeg but eventually settled in Sydney. Father Tataryn says, “My mother who was left behind basically as an orphan because her parents returned to Ukraine, went to work as a babysitter for a doctor’s children. When she got older, the matchmakers in Sydney matched her up with my father”. “This is how they met and that’s how they got married.”

He fondly remembers the cultural activities and community gatherings. “People got together in the parish hall for plays almost every Sunday. The weddings, dinners, dances they had, it was wonderful just watching the people enjoying themselves and having a great time.” Father Tataryn remembers their home used to be a gathering place for people coming from church. “My mother would bake 22 apple pies at one time, because apples were cheap in Nova Scotia, so people would come. She’d make homemade beer for the adults, and for the children, it was root beer, in gallons, we kept it in the basement! People would come and she used to treat them, and they used to talk. The men talked politics and the women talked about raising children”. There was a great camaraderie in Sydney, the Ukrainians, Poles, Anglo-Saxons, Irish, French, Italians; a great assembly of cultures, working together but retaining their own identities in their new country.

Second Period of Immigration 1918-1939

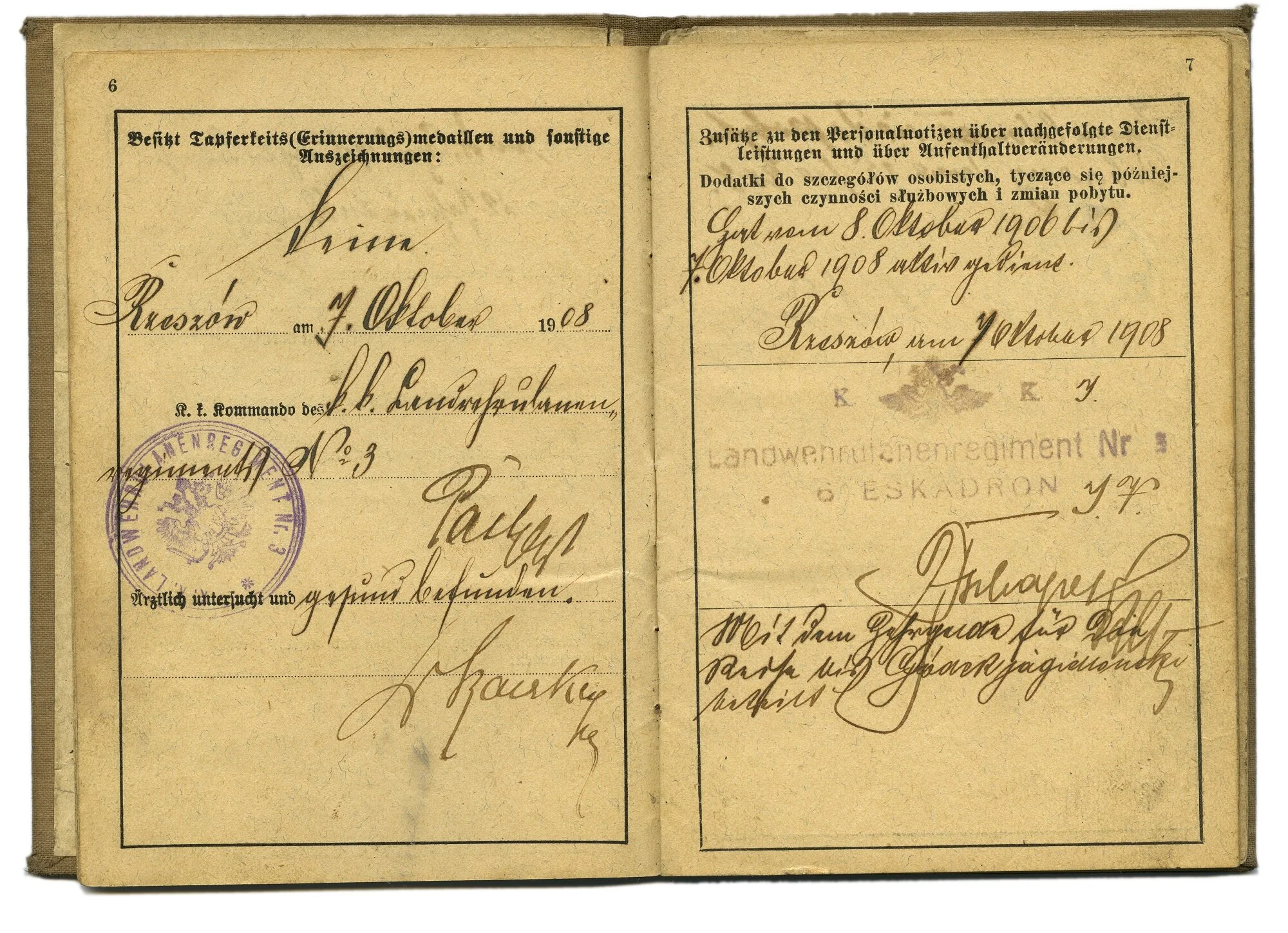

The First World War had grave consequences for Ukrainians. They were barred from entering Canada, while those already in the country were seen as “enemy aliens” for having arrived from the empires of wartime adversaries. They were monitored by government officials and some were placed in internment camps until war’s end. Between the First and Second World Wars, Canada’s immigration policy transitioned from its most expansive era in the nation’s history to perhaps its most exclusionary. In spite of major policy changes that made it more challenging for Ukrainians to be permitted into Canada, fairly large numbers still managed to emigrate during this period. It wasn’t until the conflict ended, and the economy began to improve that high levels of immigration officially resumed.

But, being permitted into Canada, was another issue. In 1919, amendments to Canada’s immigration act increased the list of inadmissible migrants and non-preferred countries of origin. Ukrainians could no longer emigrate independently and instead required sponsorship from those already in Canada.

However, the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) and Canadian National Railway (CNR) had been clamouring for homesteaders to populate the land along new tracts of rail inching across Western Canada. Newcomers would mean both temporary increases in traffic and the establishment of new settlements to intensify ongoing use of local rail lines. New immigrants arriving in Canada to fill gaps in the labour market had the promise of increased demand on the existing rail lines. As a result the rail companies petitioned Canada’s federal government for a role in the country’s immigration process. Agitation led to the 1925 Railway Agreement. The agreement permitted each company to attract immigrants from European countries deemed “non-preferred” after the war.

The Railway Agreement stipulated that immigrants must be destined for agricultural or domestic service professions. They must be morally, physically and industrially fit for Canadian conditions and the railway companies would assume all responsibility for any immigrant not employed in an approved profession.

Changes in Canada’s immigration policy during this period meant Ukrainians could be granted permission into the country based only on sponsorship by family, friends or a reputable employer. Organizations were established in both Ukraine and Canada to contend with these new immigration restrictions, admission requirements and to assist with the search for employment. The experiences of Ukrainians arriving during this second period of immigration were markedly different from those of Ukrainians who arrived before the First World War. Western farm land was no longer free, literacy had to be proved and medical examinations became far more rigorous. As Ukrainians took root in Canada, newcomers faced less uncertainty during the second period; many were often greeted in port cities by representatives of Canada’s existing Ukrainian communities. The reunion of friends and family had a positive influence on the lives of new settlers as well as established pioneers, and provided a growing sense of security for Ukrainian-Canadians.

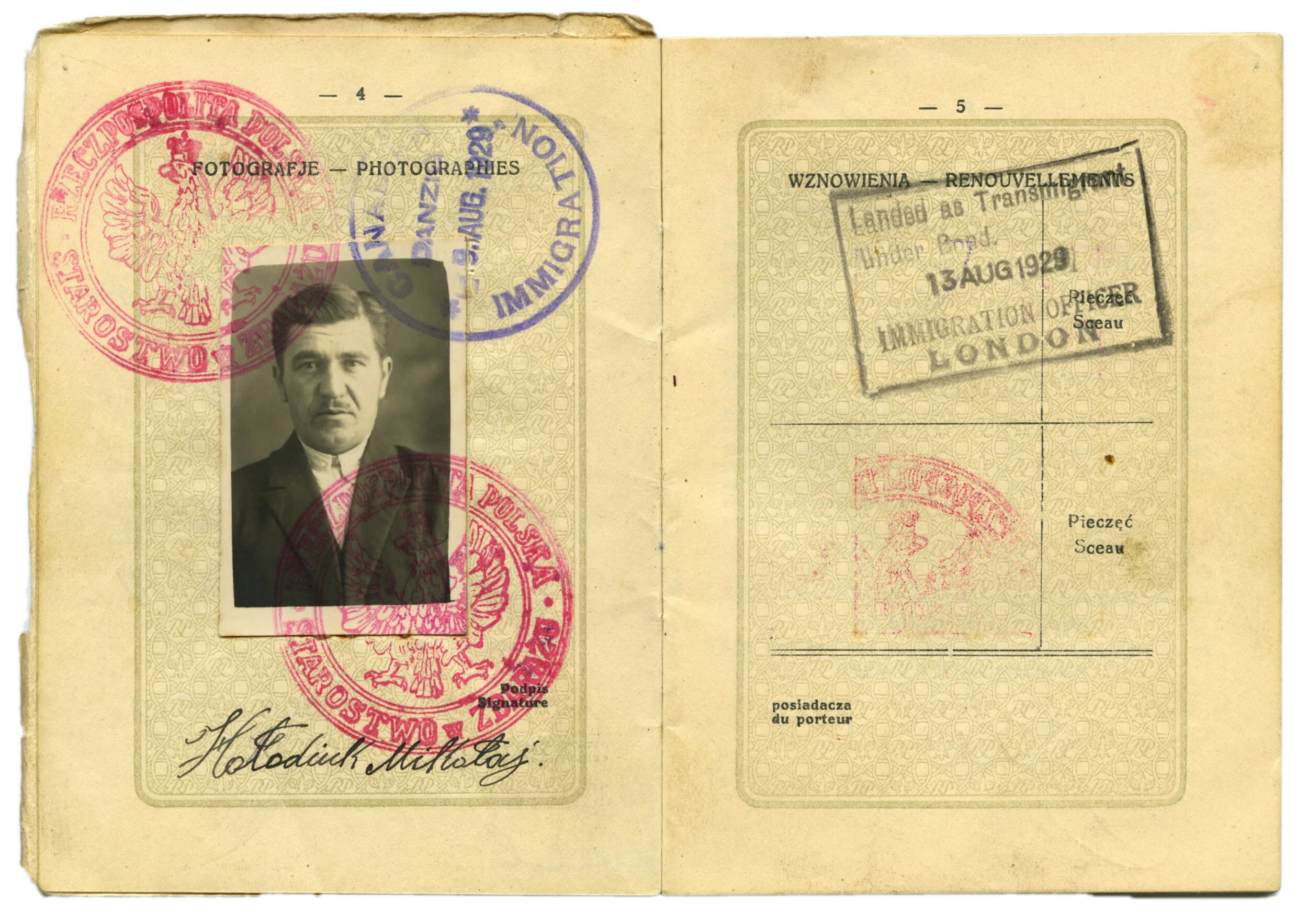

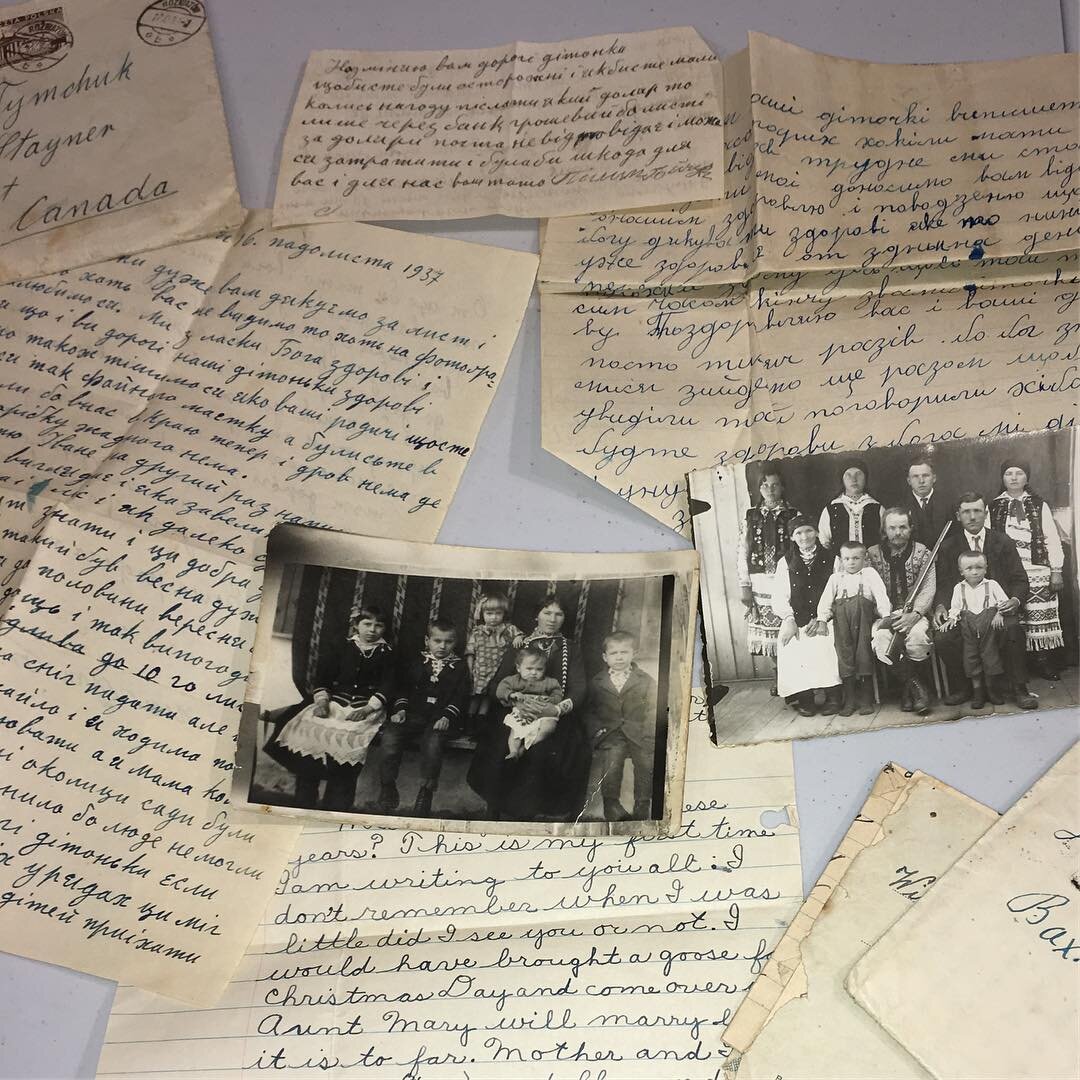

The Holodiuk Family

Emilia Pisarsky, nee (Holodiuk) was born in Ukraine, Zbarazh, in 1926. Her father Mikolaj Holodiuk came to Canada in 1929. As a farmer in Ukraine, he like everybody else who was looking for a better life and freedom, chose to emigrate to Canada. Her mother Maria stayed back in Ukraine because she was hesitant to leave the farm that she worked with her brother. As newspapers or radios were not commonplace in the 1930’s of rural Ukraine, people were not very aware of what was happening in Europe at that time. In his letters, Mikolaj wrote that there was in impending war brewing in Europe and encouraged his wife and child to come to Canada. The time had come. Emilia never knew her father as he had left for Canada when she was a very young child. She happily anticipated her voyage across the Atlantic as she was finally going to be united with here father and be able toexperience life as a family. Emilia and her mother came to Canada in in September of 1938. This was very timely as the war broke out in Europe in June of 1939. Her father was their sponsor paying for their passage to Canada.

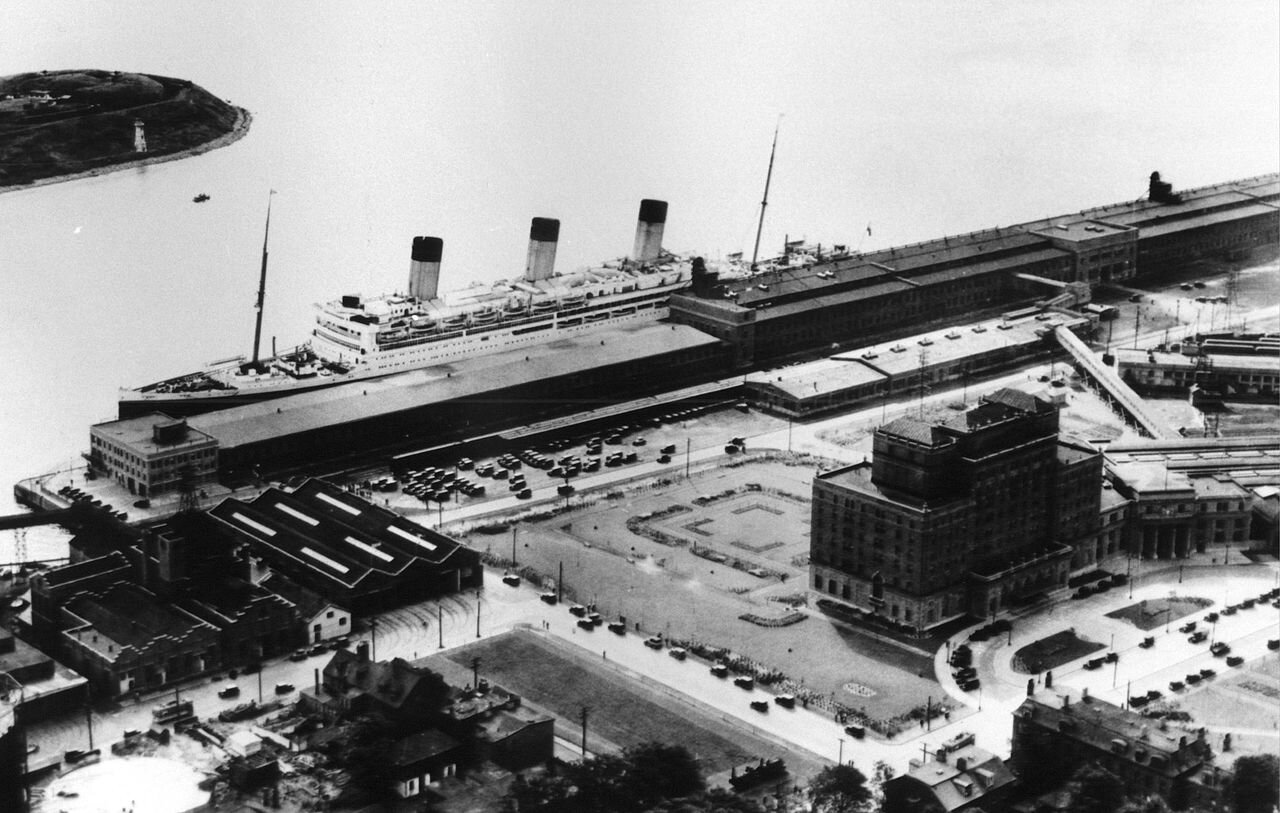

The journey involved medical exams in Ternopil’ and another examination in Warsaw as potential immigrants had to be in perfect health to come to Canada. They sailed on the ship Pilsutski; a trip that lasted 10 days, They brought with them a duvet and two pillows, some cutlery, a few knives and forks and spoons. Other than that, it was mainly bedding and clothes. They didn’t bring a lot as they didn’t have a trunk, rather a large bundle of hemp fabric tied together around their only belongings. On arriving in Halifax, they were stopped again to go through more examinations. Here they were met there by The Red Cross and Emilia remembers this as a wonderful experience because all the children were given milk, and white bread with jam; a memory that has endured.

The Holodiuk family settled in Montreal as it was an industrial city and there were jobs to be had for new immigrants. When Mikolaj arrived 10 years earlier, he stayed in the Montreal area and took a job as a carpenter. When Maria came in 1938, she got a job with a paper factory recycling paper. Settling in the Frontenac district near Iberville, the Holodiuk’s life in Canada began. (click here for full interview)

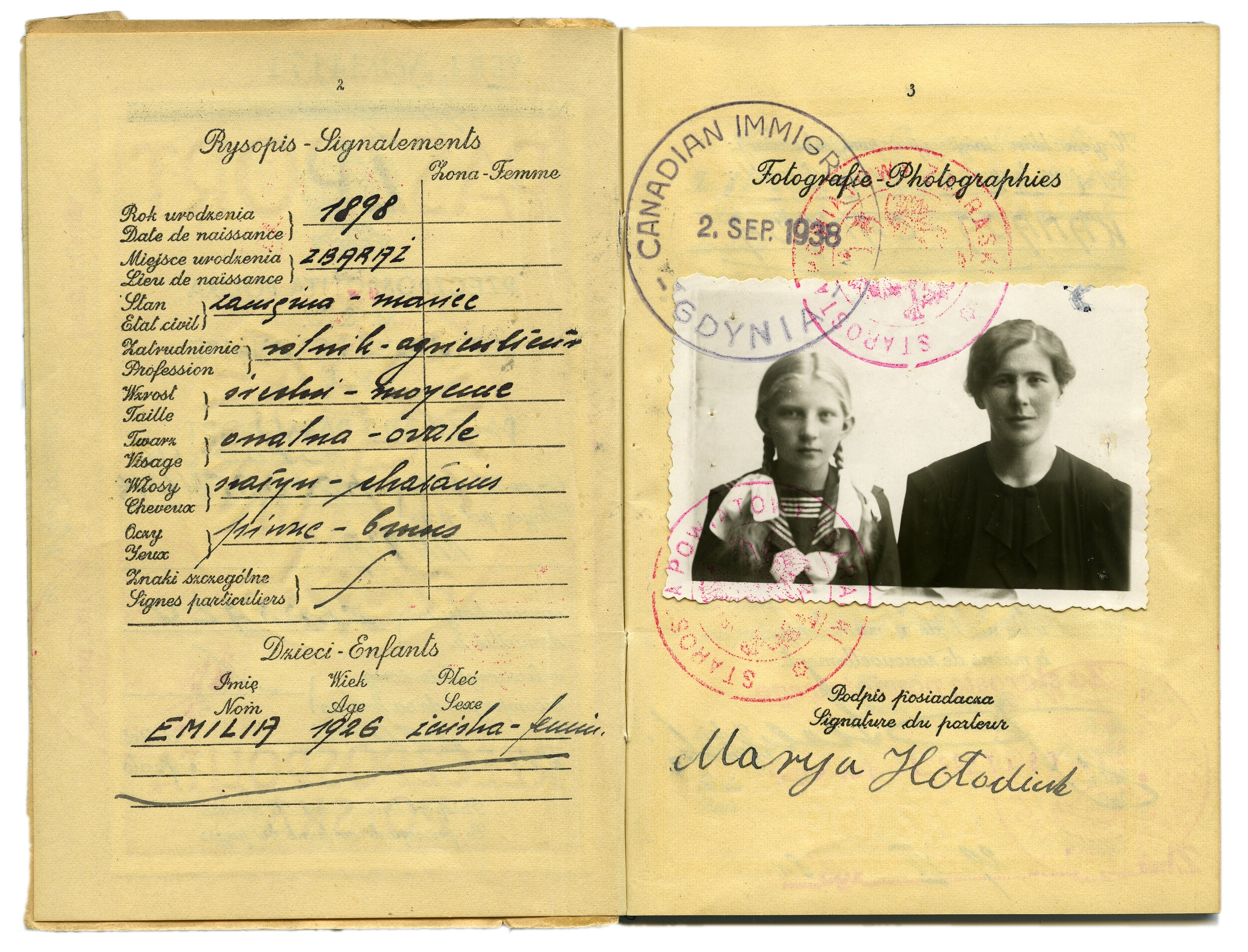

Sydney, Nova Scotia, 1924. After World War I, it became increasingly difficult for Ukrainians, among others, to immigrate to Canada. Ukrainians were no longer able to enter the country independently, and instead required sponsorship from relatives, friends, or employers in Canada. This document from 1924 illustrates how Katyryna Marko, seeking entry to Canada, was required to marry a bachelor in Sydney, Nova Scotia, named Harry Huk, in order to immigrate. It shows Harry agreeing to marry Katyryna within a month of her arrival to Canada. If these terms weren't met, his $100.00 deposit would not be returned to him.

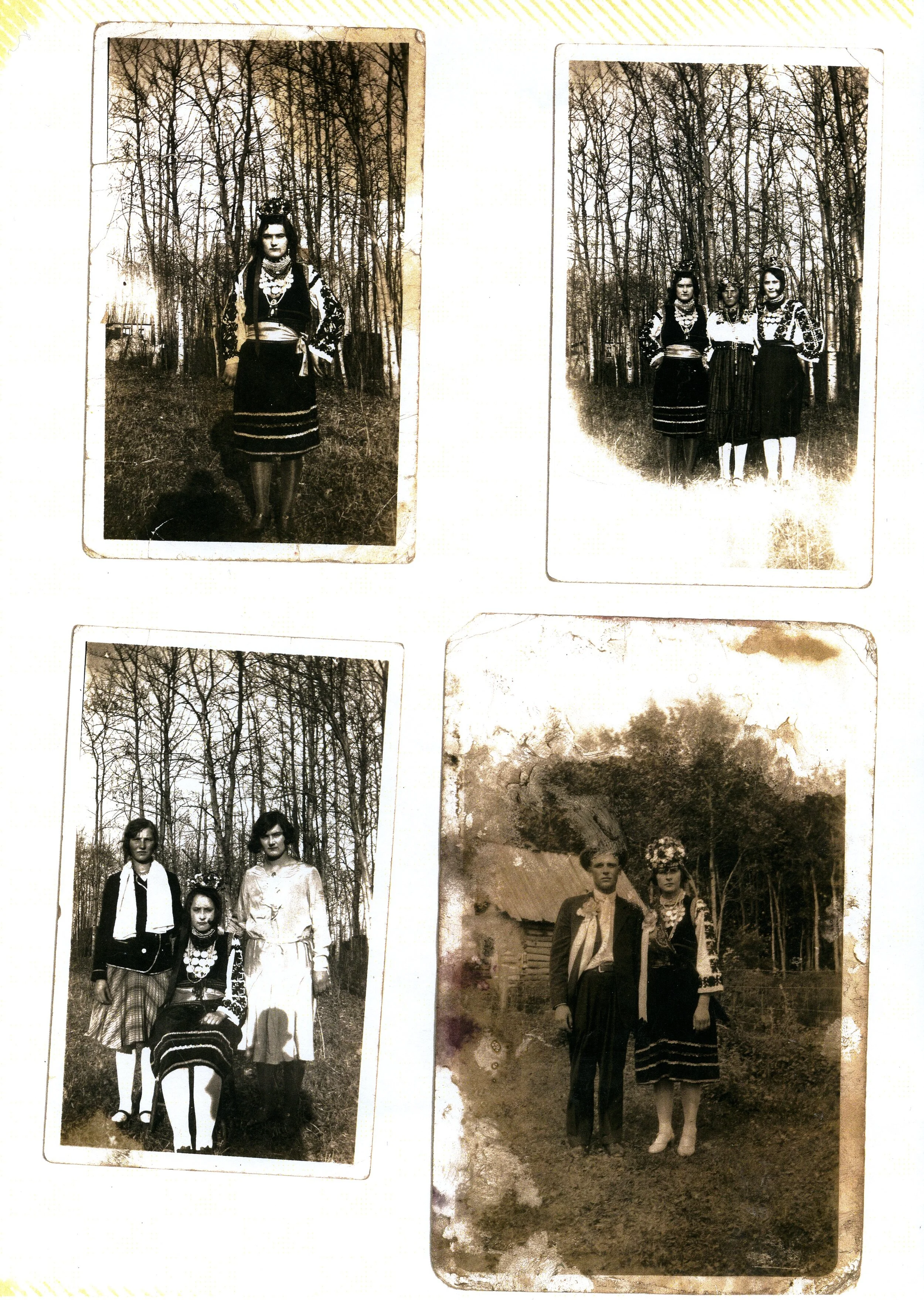

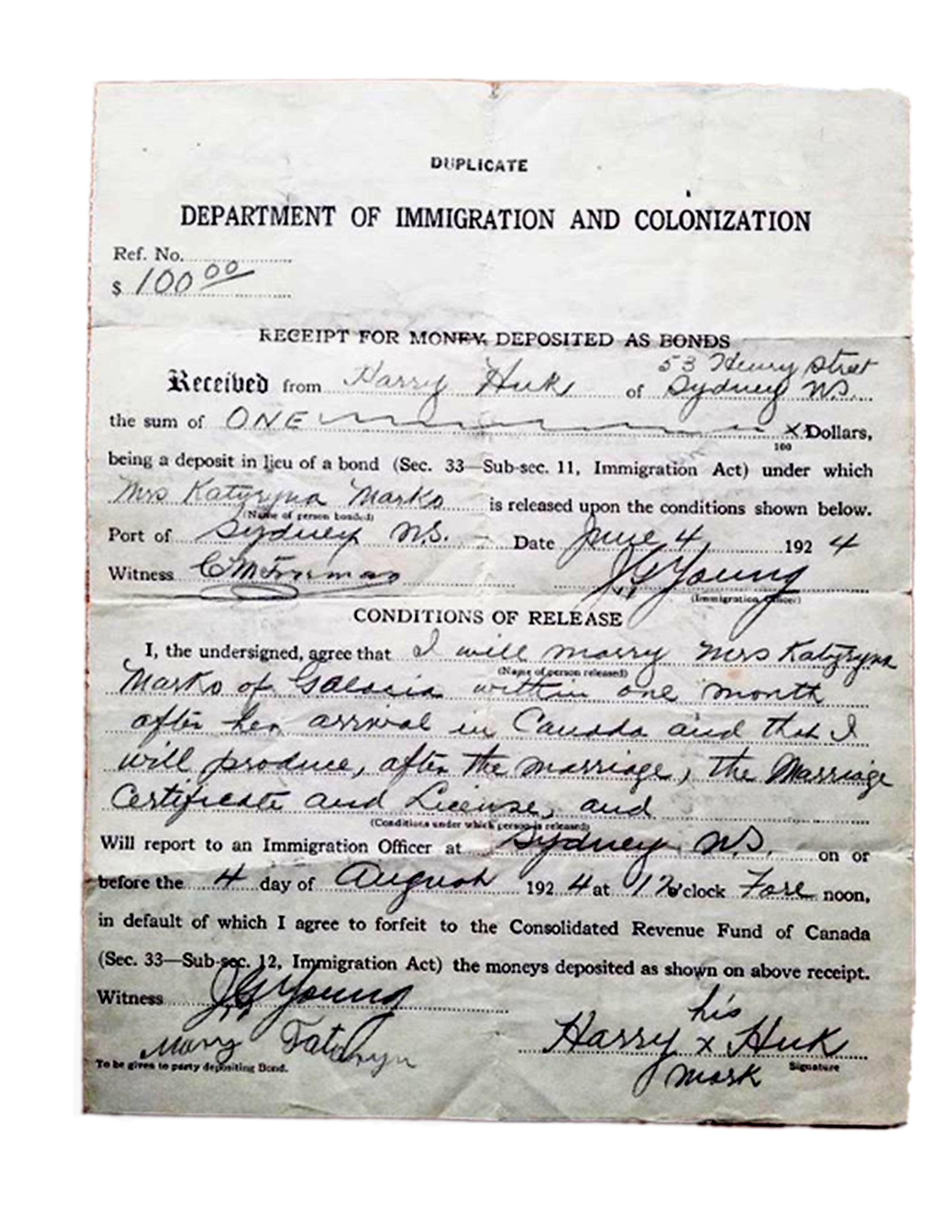

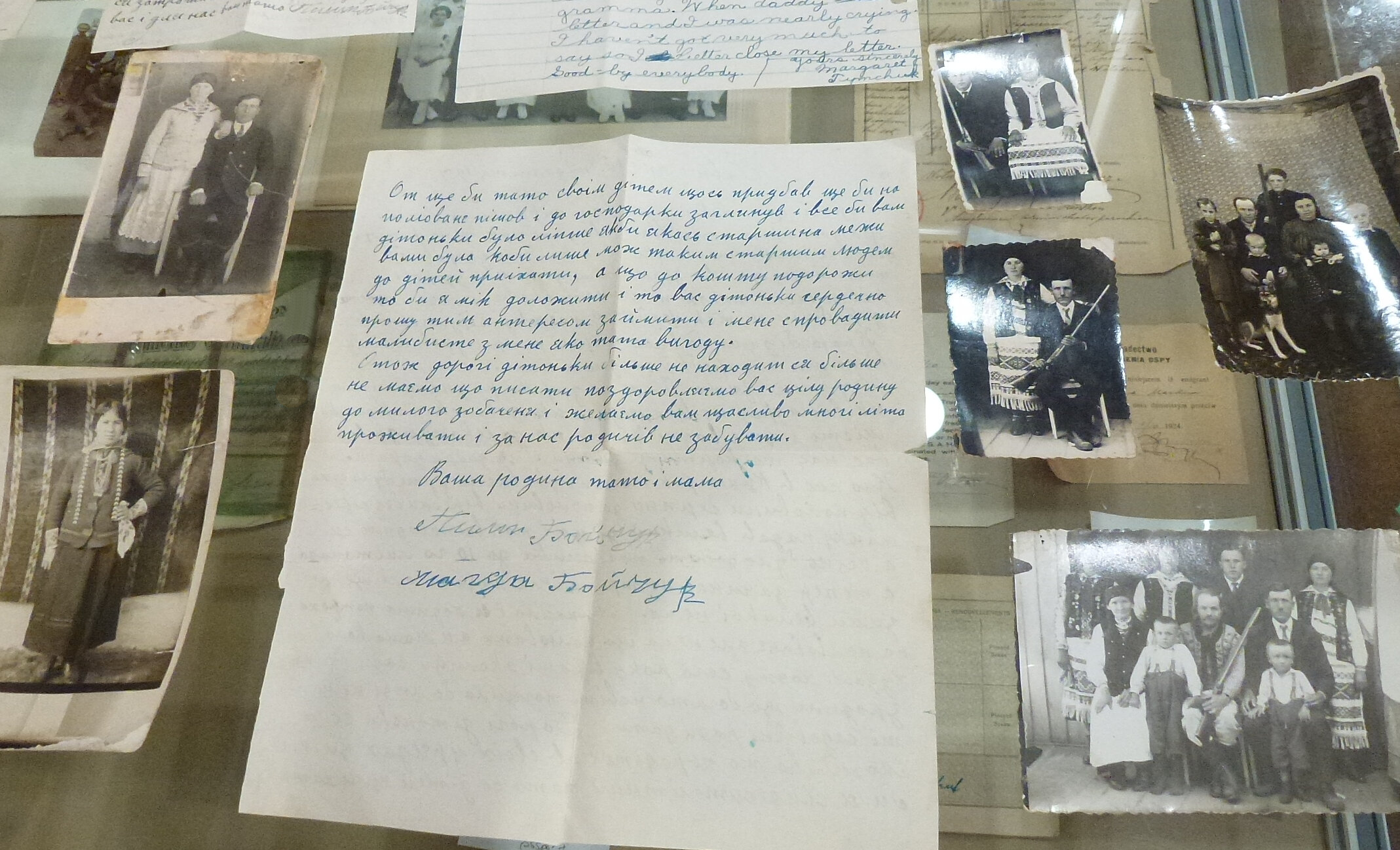

In 1930 Mary Tymchuk immigrated to Canada with her four children. She was met by her husband John who had arrived two years earlier. Once united in Canada the Tymchuk's used written correspondence to keep in close contact with their relatives back home. In one letter, sent by Mary's father Pylyp, he asks "...is it possible to seek advice from your governments to find out if a 70 year old father could come to Canada to join his children?” This letter and dozens more were recently donated to the Museum by Patricia Ryan (nee Tymchuk) along with numerous photos and two of Mary's beautiful sorochky (shirts).

This sheepskin coat was worn by Jefim Omelchenko from the Volyn' region of Ukraine. Jefim emigrated to Canada in 1937 with his wife and two young daughters. The family settled in Onoway, Alberta where they purchased land and farmed it until 1941. The following year they moved to Grimsby, Ontario where they bought land and cultivated a successful fruit farm. This beautiful sheepskin kept Jefim warm during the bitter Alberta winters. It not only reminded him of his home country Ukraine, but also sheltered him during the cold winters in his new country Canada. Jefim’s wife Nadia carefully mended the sleeve when it became worn.

During artifact research, the Museum staff was able to reconnect this artifact with the original donor's granddaughter, Lesia Korobaylo who happens to be one of the Museum's dedicated volunteers. Unbeknownst to her, the Museum had been carefully looking after her grandfather's coat for the past 45 years!

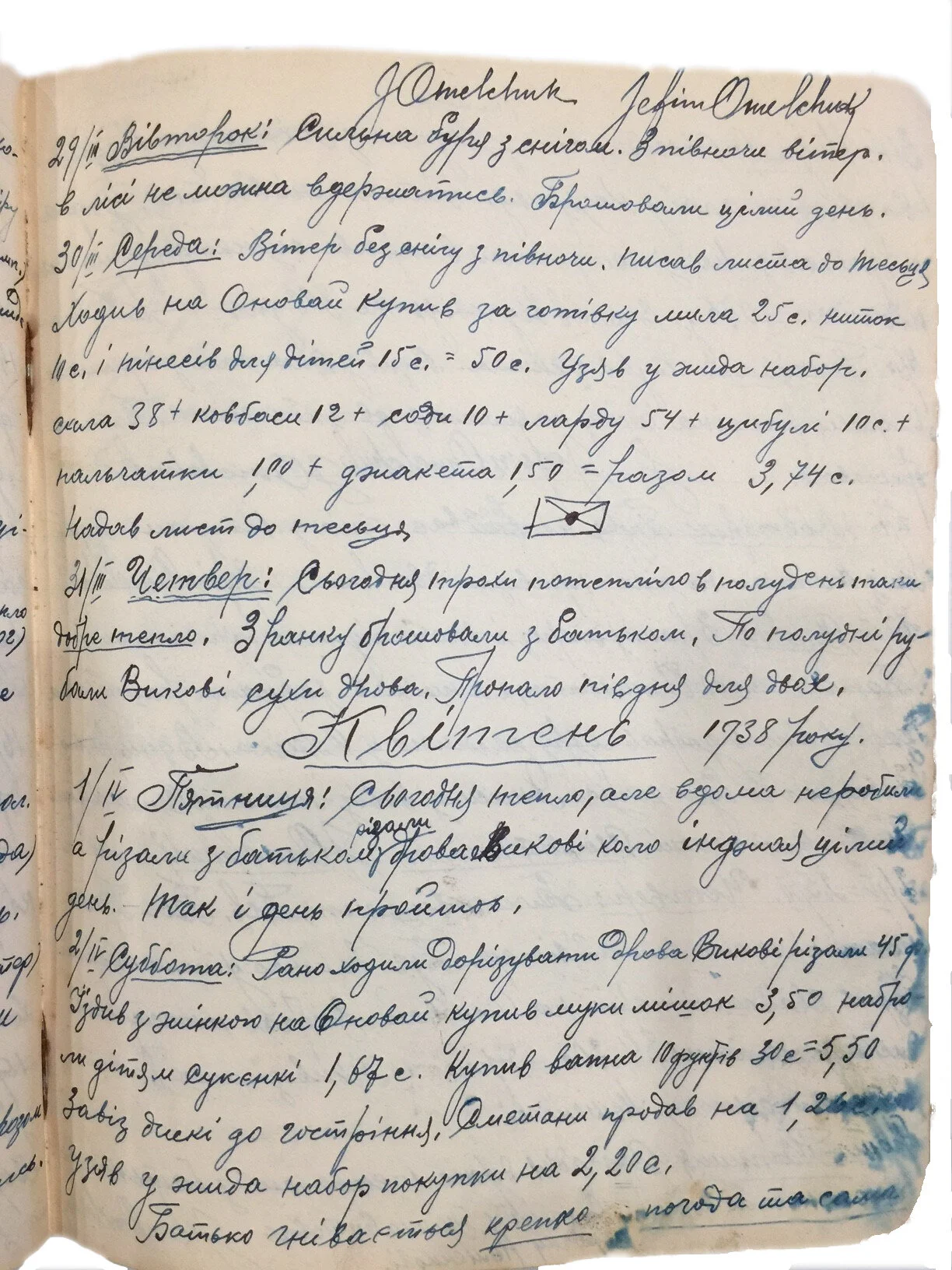

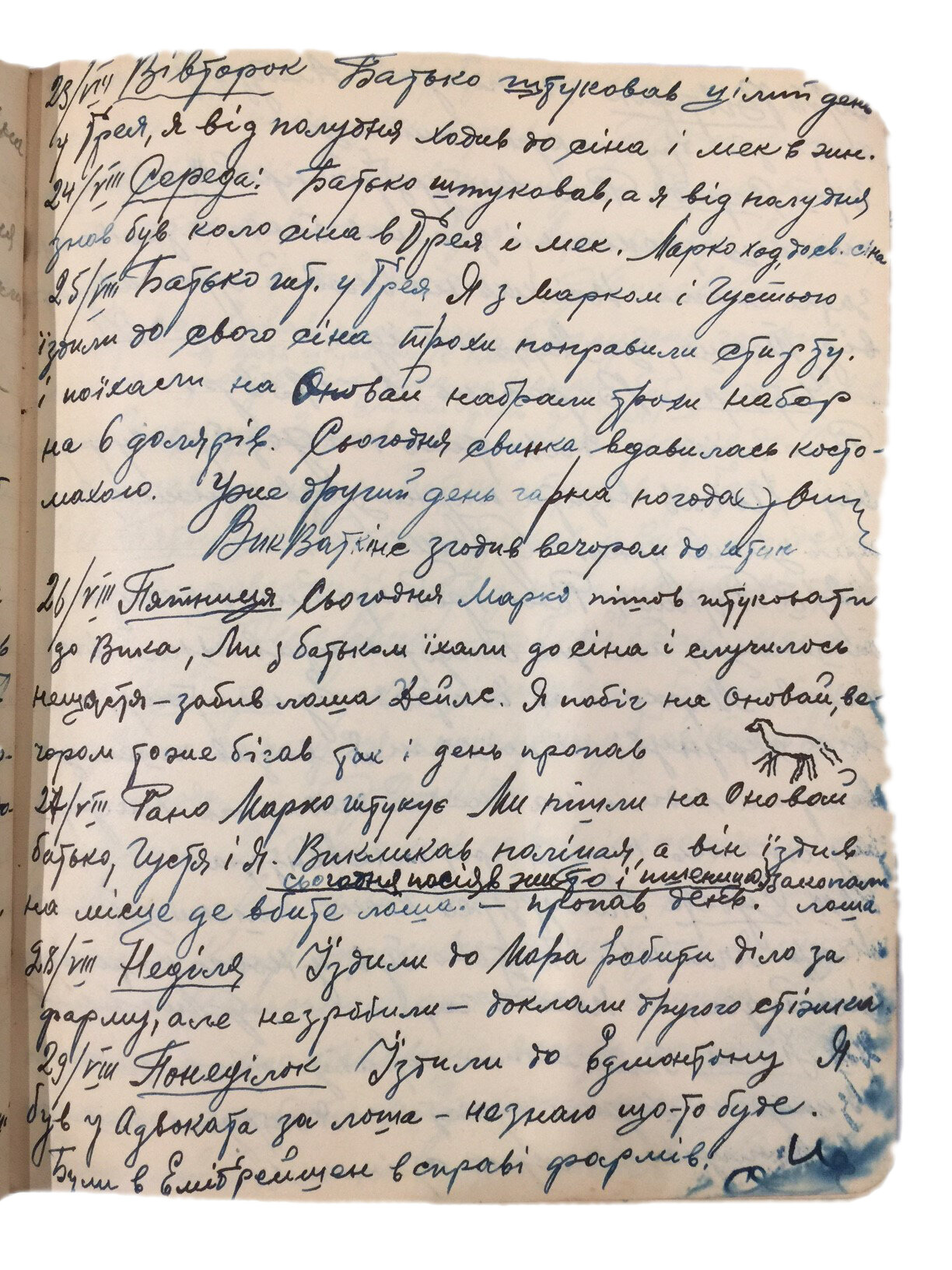

Below, Jefim (pictured) kept a diary of each day’s events and the world around him.

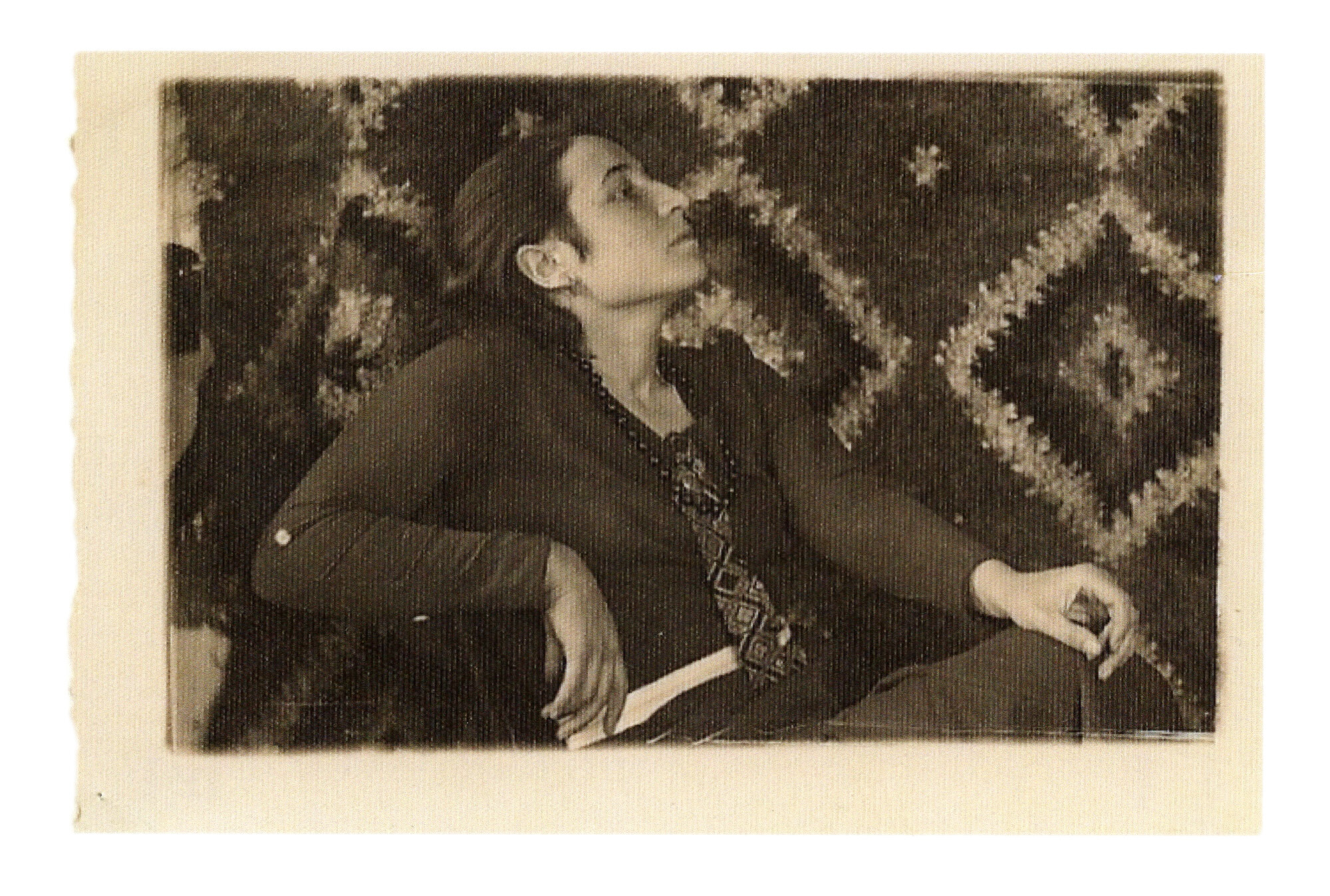

This beautiful lizhnyk (bedspread) was acquired by philologist and folk art collector Leonida Zajszla (pictured here) in the 1930s. She later passed the item onto her brother and his family before she was imprisoned so they could bring it with them to Canada. This lizhnyk was donated by Iryna Bell (Leonida’s niece). Leonida remained in the USSR actively resisting Soviet rule - an effort that, like for so many, resulted in arrest, torture, and incarceration in a concentration camp.

Third Period of Immigration 1945 - 1960

The third period of Ukrainian immigration to Canada was triggered by the devastation of the Second World War. Ukrainians found themselves displaced in Western Europe, because of the forced labour schemes of Nazi Germany and the fear inspired by an advancing Soviet Red Army. In the wake of this global humanitarian crisis, Canada amended its immigration policy to deal with the innumerable refugees who were not only displaced by war, but also unable to return home due to the Soviet regimes that took root across Eastern Europe.

Those unable to return home by war’s end were housed in Displaced Persons (“DP”) Camps. These camps were established across Germany and Austria, operated by allied occupying forces and relief agencies to assist in the repatriation or resettlement of displaced refugees. Although intended for temporary use, countless DPs called these camps home for as many as eight years. Camps began as multicultural compounds, but over time there was a natural shift to the formation of community groupings based on ethnicity, religion and geography. Camp administration provided DPs with shelter, food and basic healthcare but the residents themselves established a number of diverse self-governing institutions which reflected their national character and aspirations.

In Canada, immigration was viewed with anxiety in the immediate aftermath of war and stabilizing the economy was the most important post-war issue. Surprisingly, the Canadian economy made an immediate recovery, attributed to pent-up consumer demand, an increase in foreign demand for Canadian natural resources, and large-scale private investments into the manufacturing and natural resource sectors. Although a great humanitarian crisis emerged from the war, it was largely economic factors that revived post-war immigration to Canada. There were employment deficiencies that needed to be filled and consumer markets that could be expanded by the arrival of new immigrants.

Like other ethnic communities in the country, Canada’s Ukrainian community took on active roles in the aid and resettling of their fellow compatriots. In Canada, Ukrainian-Canadians lobbied for the cause of refugees and raised funds to assist those overseas. Local organizations like the Ukrainian Canadian Congress actively pressured the Canadian Senate, while the Ukrainian Canadian Relief Fund provided financial resources for resettling Ukrainians in Canada. During this period, Ukrainian immigrants entered Canada primarily through employment programs or family and government sponsorship. Selection criteria for employer and government sponsorship was guided by economic self-interest, political bias and racial prejudice as Canada attempted to reconcile labour demands with asylum. According to Canada’s then External Affairs officer, John Holmes, refugees were selected “like good beef cattle.” Employers in mining, lumber, agricultural, construction and manufacturing sectors acted as recruiters, bringing in DPs for strict contract employment positions.

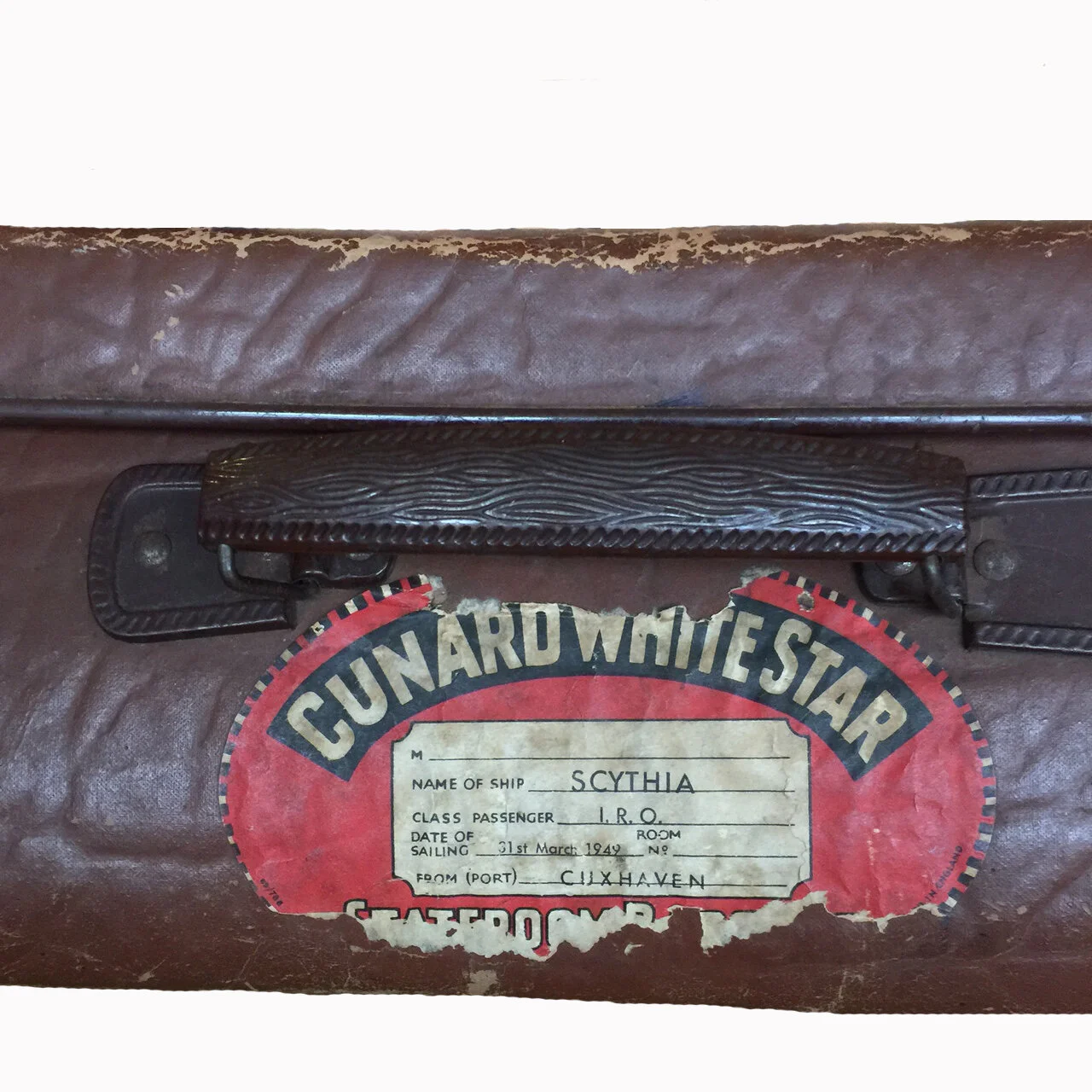

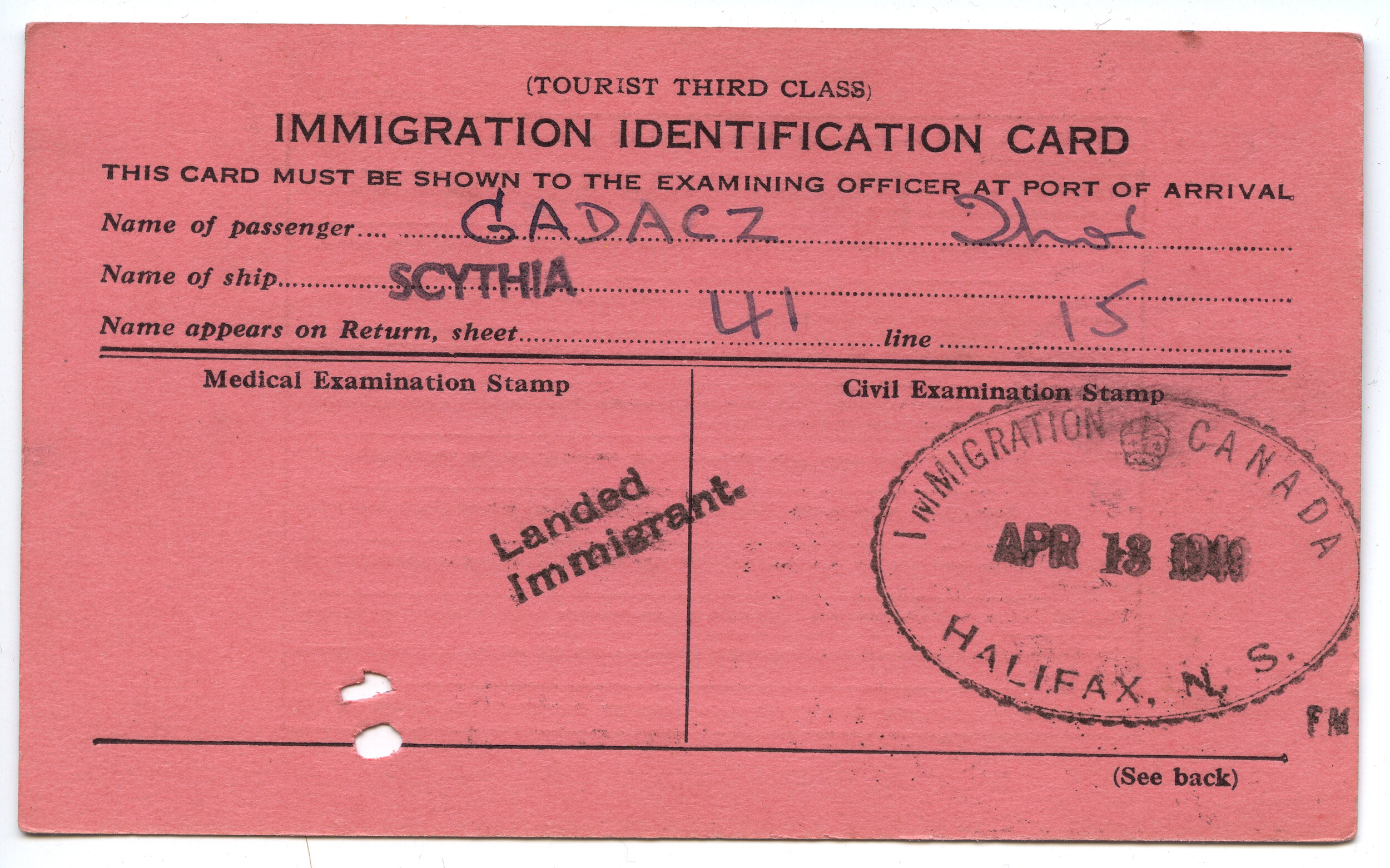

The Gadacz family

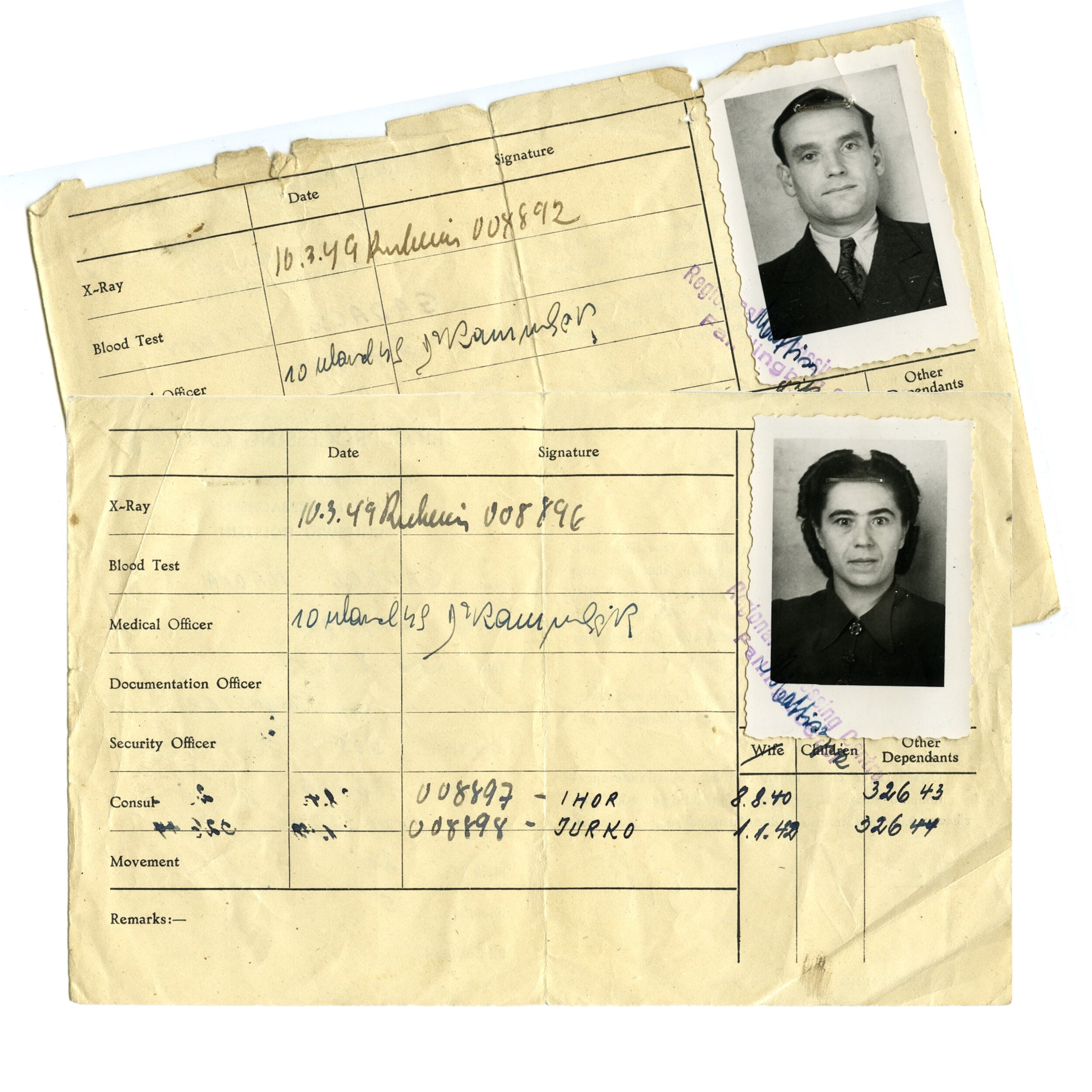

The Gadacz family (father Stefan, mother Nadia and children Yurij and Ihor) came from Sloboda Zolota, which is the township of Berezhany, near Ternopil’, Ukraine and immigrated to Canada in April 1949. They were refugees after World War II fleeing the Russian advance into Ukraine as the KGB had marked Stefan and his family for exile to Siberia. To avoid that fate they set out west towards the Hungarian-Czech Slovak border but ended up in German territory where their horses and wagons were confiscated. They were put on a train for Germany where they resided for the next 4 years in various locations including DP camps. Ihor recalls a community established by the Ukrainians which included camps and schools for children, a church where they celebrated Easter and Christmas and organizations where the adults shared in camaraderie. He vividly remembers the concerts and the special occasion when the Bandurist choir came to perform.

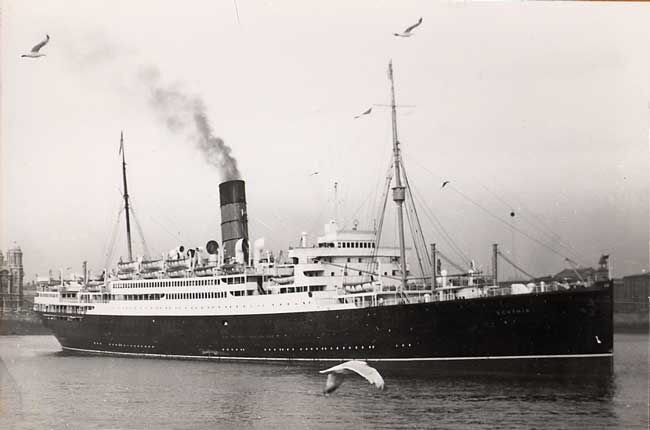

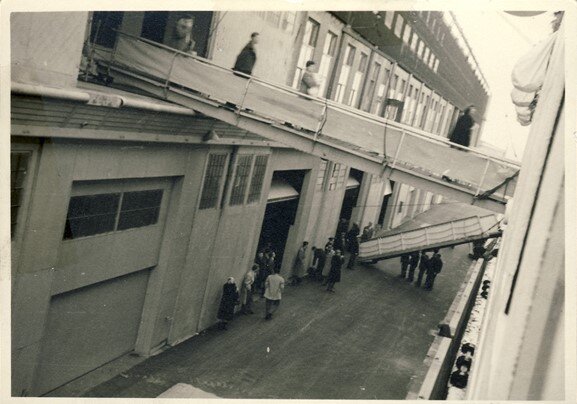

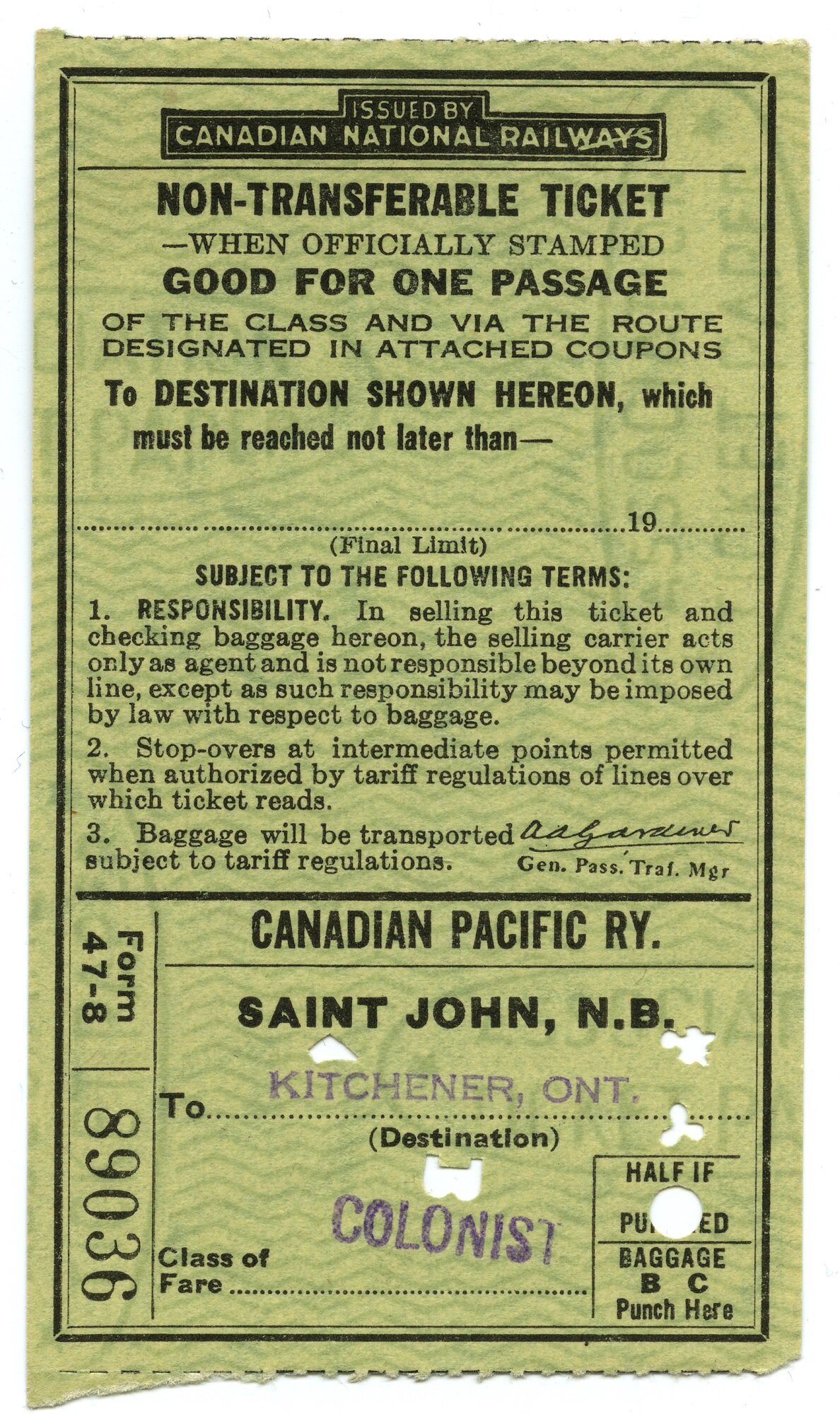

The idea of coming to Canada came about because the Gadacz family kept in touch with relatives who had immigrated to Canada in the 1920s. But in 1947 - 1948, Canada wasn’t accepting any refugees from Germany, so the family signed up to go to Australia as they did not want to remain in Europe given the post-war unrest. By 1948 - 1949, the government of Canada had changed their policy and started accepting immigrants, so relatives in Kitchener sponsored the family and arranged for transport overseas. They came by ship on the Canard steamship lines, landed in Halifax and took a train to Kitchener where their relatives lived. Stefan worked in construction for a year, and Nadia worked as a cook in the restaurant their relatives owned. The family lived in the basement of this restaurant. After a year they realized that most of their immigrant friends and acquaintances lived in Toronto, so in the summer of 1950 the family moved there.

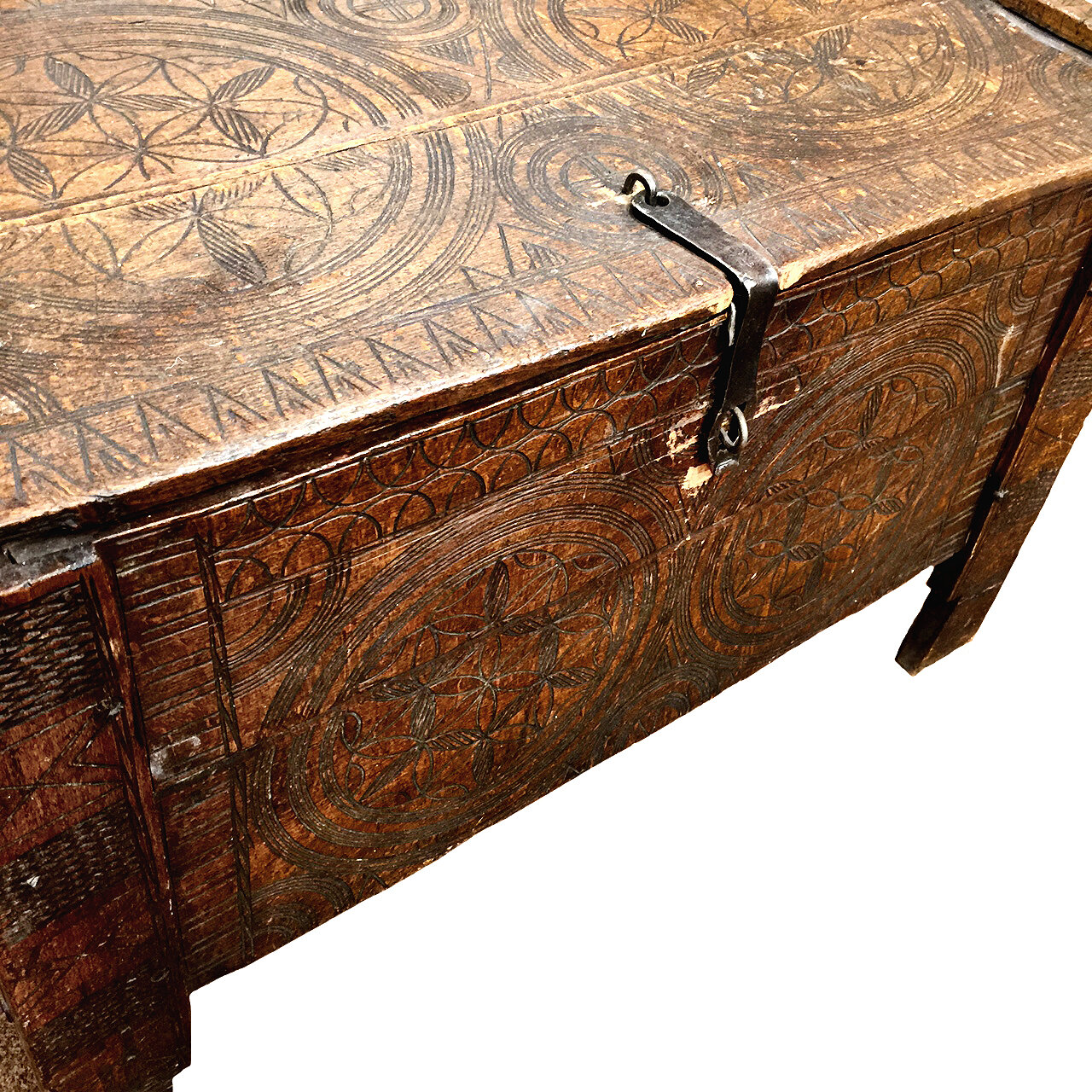

Ihor remembers that before travelling to Canada, his parents had a sturdy wooden trunk constructed by a friend who was a carpenter. The family used it to store blankets and linens. This was the trunk that would bring many of their belongings to Canada. Along with it, they packed a cardboard suitcase, acquired in Germany, with exquisite decorations that adorned the family Christmas tree for many years.

The Gadacz family, like many Ukrainians, valued Canada as a land of great opportunity as well as a place to maintain important family traditions. Ihor Gadacz, who was interested in science and the idea of helping people was fortunate to pursue higher education and became a doctor. (click here for full interview)

The Kylmynyk Family

Stefan and Larissa Kylymnyk left Ukraine and ended up in a Displaced Person’s camp in Austria from which point they immigrated to Canada.

The Kylymnyks and Oleksa Rewa had a good life in Ukraine. They had a nice house, advanced education, professional jobs and had achieved a lifestyle they enjoyed. But life was unpredictable and the war forced the family to make difficult and irrevocable decisions. They would start their lives over again in Canada bringing with them personal and important momentos. With these few treasures they started life anew.

Journey to Canada Series | Dr. George Rewa

Click to view the interview (28:26, English)

One of these treasures is this unique kylym which was made between 1710 and 1720 in Yakushynets', Ukraine, by numerous female Ukrainian serfs serving a Polish nobleman. Working under a master kylym designer known as "Ivan," the women made all parts of the kylym themselves - even the threads and dyes. The kylym was rescued from the manor by a servant named Yaryna Kharchuk when the estate was set on fire by local villagers in retaliation against the nobleman, who had assaulted numerous young local girls. The kylym was given to a local priest, who then passed it on to the marshal of Podillia, Oleksandr Rusanovs'kyi and through his family to the last surviving member. The kylym was then passed on to Olga Kulyk-Poplavs'ka, and eventually ended up in the hands of a professor Stepan Kylymnyk who brought it to Canada. Apologetic for some of the visible wear on the kylym as he was donating it, Professor Kylymnyk explained that he had used it to keep his children warm while escaping war-torn Ukraine on the family’s way to Europe.

It is worn and tattered in a few spots but incredibly beautiful for an artifact of its age and its unique provenance. The UMC Ontario Branch thanks the Kylymnyk and Rewa families for this treasure.

Fourth Period of Immigration 1960 - 1991

Ukraine

Although the Second World War was long over by the 1950s, tension between east and west was steadily growing. The vast majority of Eastern Europe was absorbed by the Soviet Union. With the absence of direct military conflict, this period of tension, commonly called the Cold War, lasted for more than 50 years before the Soviet Union’s complete dissolution in 1991. The entirety of Ukrainian territory fell under Soviet control – subjected to authoritarian rule, cultural repression, surveillance, economic hardship, and assimilation into Soviet communist society. Emigration from the Soviet Union was almost unheard of as the Iron Curtain fell across Europe.

The Russian language was installed as the language of work, public life, academia and politics across the Soviet Union. Ukrainians clung to their cultural, religious and historical identities, which were forced underground by Soviet authorities. Declaring oneself a champion of Ukrainian culture could lead to exclusion from higher education, confinement to a psychiatric hospital, imprisonment and even exile. Consequently, human rights abuses were commonplace in the Soviet Union.

Glasnost and Perestroika

Prior to 1986, obtaining permission to travel abroad for personal reasons was nearly impossible. Inhabitants of the Soviet Union were subject to an almost closed-border policy, with emigrants trying to emigrate before 1986 being deemed “deserters.”

By the mid- 1980’s, the Soviet Union’s system was not working as citizens craved freedom and opportunities beyond the Iron Curtain. Perestroika or “restructuring” introduced market-oriented reforms in 1986 with measured amounts of free enterprise permitted. Glasnost, or “openness” created a dialogue between the state and the disgruntled public. Freedom of speech slowly flourished as glasnost established a platform for citizens to voice criticisms of the regime and its leaders without fear of persecution.

Under the weight of its own failures, the Soviet Union came to a full collapse, allowing formerly buried nations to emerge. By 1991, the Soviet Union came to a complete collapse. A referendum on Ukraine’s independence was held December 1, 1991. 92.3% of voters approved the declaration and on the same day Ukraine’s first president was elected. On December 2, 1991, Ukraine became a globally recognized state.

Canada

Canada’s immigration policy during this period revealed a growing preference for selection and regulation. Canada’s new Immigration Act, 1976 introduced principles including immigration as a means to: enrich Canada’s multicultural fabric, reach demographic goals, facilitate family reunification and grow the economy. Under the new act, prospective immigrants fell into three classes: family, refugee and independent. Immediate relatives of Canadian citizens and permanent residents could apply as family class immigrants. Those subject to persecution or displacement from their home were permitted to apply as refugee class immigrants. Those who did not fit into either family or refugee classes could apply as independent class immigrants subject to assessment under the “point system.” This system included categories such as age, education, occupation, experience, language and personal suitability.

Immigrating to Canada after 1986 became challenging. After the introduction of glasnost and perestroika, which improved the personal freedoms and human rights of Soviet citizens, entry to Canada became more of a challenge because the USSR was no longer perceived as a communist dictatorship violating the basic rights of its citizens. Those wishing to flee could no longer claim refugee class status in Canada’s immigration system. Future applicants had to demonstrate their worth to Canada as independent class immigrants if they lacked relatives in the country capable of sponsoring them.

The Story of Ukrainian Students in Poland.

A number of young Ukrainians living in Poland travelled in Europe during the summer of 1981. Once in Austria, they applied for political asylum on the basis of discrimination of Ukrainians in Poland. Their circumstances caught the attention of many Ukrainian organizations and individuals in Europe and Canada who provided assistance. Eventually the majority arrived in Canada in 1982 through the efforts of the Canadian Ukrainian Immigrant Aid Society, among others.

The boots, parkas and knapsack were provided to the students from Poland while they were in Austria by a generous member of the Ukrainian diaspora. Each of the young men received the same military style parkas, boots and knapsacks whereas the young women had a choice of styles. The parkas, boots and knapsack pictured here were loaned to the Museum by Bohdan Szubelak.

My Canada started here.

Maria Jacyla, a graduate of cultural studies in Poland, bought her passion for Ukrainian art history to Canada in 1982.

In her suitcase (pictured here) she brought two books on Ukrainian art, three pieces of her great grandmother’s embroidery and her graduate diploma. Also pictured are several letters Jacyla received in her first years in Canada.

Maria was sponsored to Canada by the Ukrainian Women’s Association of Canada, Kniahynia Olha Branch and upon her arrival was presented a copy of Twenty Five Years of the Ukrainian Women’s Association of Canada 1926 – 1951. The photographs (pictured) show a number of Jacyla’s “firsts” in Canada. Her first home, her first job, her first class. “My Canada started here” Maria has nostalgically recollected about the intersection of Bathurst and College Streets in Toronto.

TRUNK TALES:

LEAVING HOME … FINDING HOME

Our ancestors arrived in Canada during four periods of immigration. Each trunk and suitcase they carried had its own fascinating history of hardship, loss and, ultimately great hope and joy for the future. You have met some of these families through their photos, passports and compelling personal accounts. These Ukrainians who left their homes for a new country brought with them, not only cherished mementos, but also traditions and an intangible culture that continues today in their chosen home of Canada.